Alexander Mackie Younger

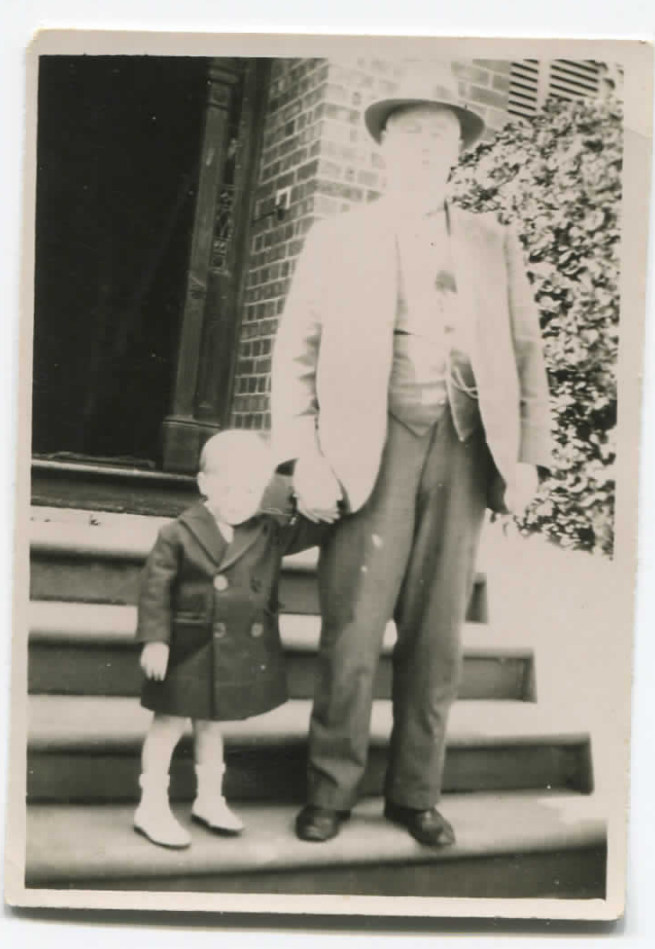

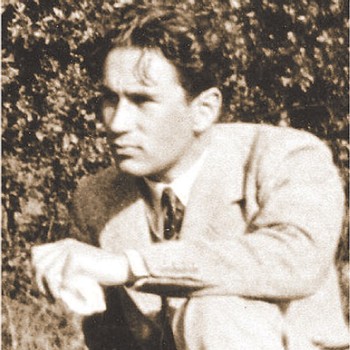

Ardoch’s visionary creator was Alexander Mackie Younger (1882–1952).

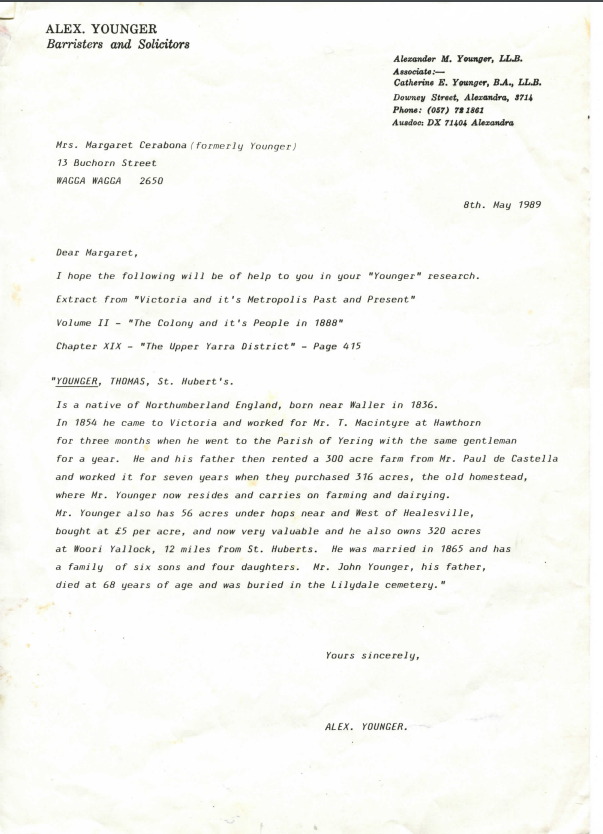

Alexander Mackie Younger made his fortune from hard work and the ability to see opportunities where others could not. Born in stables on the family’s leased property at Yering in Victoria’s Yarra Valley, he was one of nine children but his innovation and drive ensured his success and he rose to prominence quickly.

Having already worked on housing developments in Melbourne; when the mansion, where Ardoch now stands, came on the market he saw the opportunity – and potential – of building flats. His great-granddaughters speculated that because he was already in the building trade he would have known when suitable properties were coming up for sale.

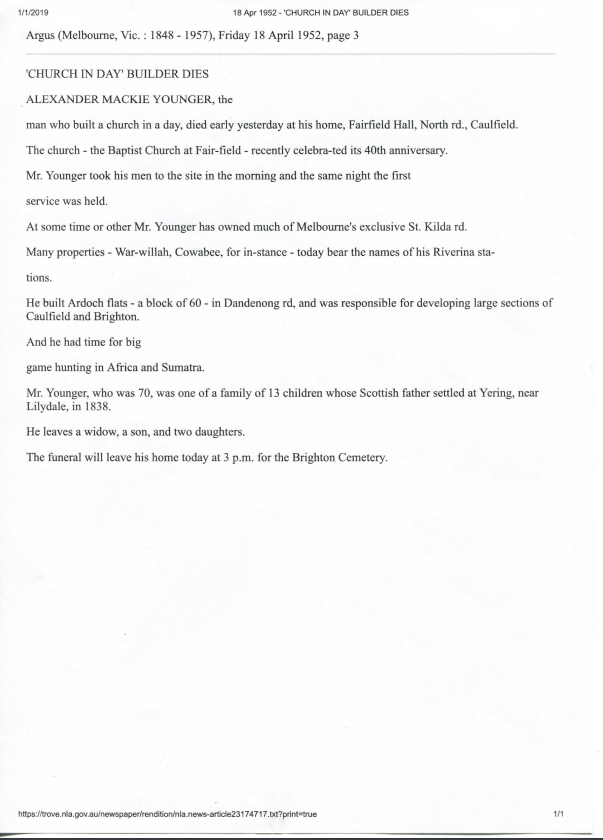

He was a thinker and innovator and one way in which he exercised his ideas was through the financial model of grouping houses together. He had already constructed houses around his family home in Caulfield which he’d purchased in 1912. He was particularly busy from then until 1918. When he died in 1952, The Argus noted that he was remembered as the man who built a church in a day (the Fairfield Baptist Church). ‘At some time or other Mr Younger has owned much of Melbourne’s exclusive St Kilda Road. Many properties … bear the names of his Riverina [sheep] stations … [He] was responsible for developing large sections of Caulfield and Brighton.’[1]

Developing land and constructing flats was a relatively new evolution in housing for Melbourne during the 1920s. To overcome a negative perception of living in flats, Younger made his designs grander and bigger as he experimented with a hybrid model of living. His ideas also made housing more accessible to less wealthy people, perhaps harking back to his upbringing.

Although the Ardoch development is credited as being part of the early ‘garden city movement’, Younger was yet to travel to see these developments first hand. His great-granddaughters believe the ideas came from reading newspapers and journals. He ‘always wanted to innovate so he was looking at other ways of being communal … We just think he wanted to be innovative and he looked for ways it was being done over in the Old Country. He obviously felt his ties back to the Old Country.’ While his early work was Federation style, Ardoch is Arts and Crafts style with each building being slightly different although the site was designed as a whole. As he wasn’t an architect, his great-granddaughters don’t know if he created the designs himself or brought others in to assist.

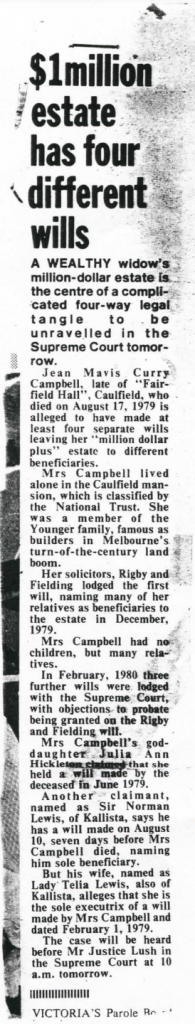

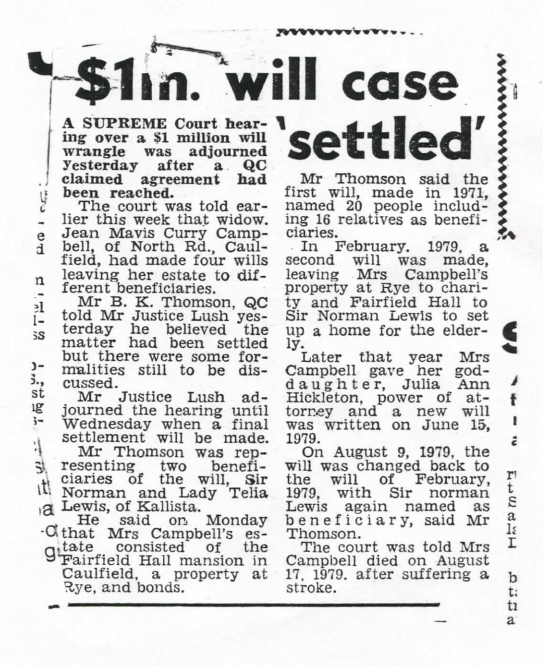

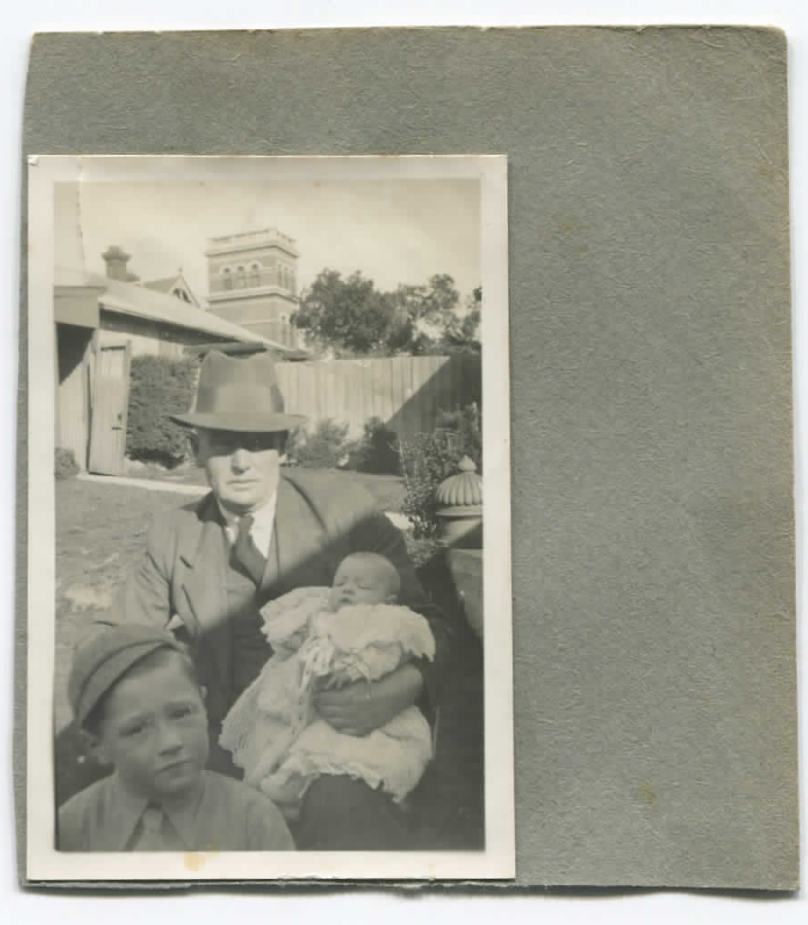

Evidently, Younger was perceived as an intimidating man. He wasn’t charismatic. Some described him as ruthless and mean-spirited. A selfish Presbyterian. A teetotaller. Frugal. Even in his old age, his daughter-in-law remembered him scraping concrete off bricks so they could be reused. But there was something about him that drew people to him. His family knew he was capable of being kind. However he might be described, Younger had a flamboyant personal life marked by tragedy and a scandal. His first wife, Elizabeth, died from an accidental gunshot wound in 1918. A second, disastrous, marriage in 1923 lasting only ten days, became press fodder during the mid-1920s. The couple were divorced by early 1928. He went on to marry the children’s nanny; the woman with whom his second wife asserted he was having an affair throughout their short marriage.

Between 1932–35, long after Younger sold the Ardoch development, he finally travelled overseas – to Kenya and around England – but the trip changed the family forever. By this stage, Younger was a wealthy man so he took his four adult children and their families with him and they lived overseas for some time. It was in Kenya, while hunting big game, that his eldest son, Jack, was accidentally shot. Jack had been working with his father and was in line to take over the family business. By all accounts, Younger was devastated and brought up Jack’s son in the absence of his father. Younger’s great-granddaughters recall that this trip, ‘changed everything about us. And we think it might have stopped his drive for his building empire.’ For the final 20 years of his life, Younger did not do any building work. Ardoch remains evidence of his significant legacy to Melbourne’s development.

[1] The Argus, 18.4.1952, p.3